Rooted in Wonder

Image courtesy of Sarah Lebeis, University of North Carolina

Image courtesy of Sarah Lebeis, University of North Carolina

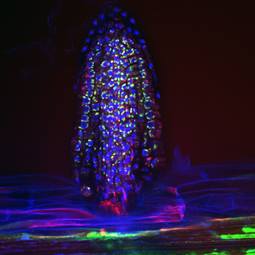

A fluorescent micrograph capturing the presence of bacteria (shown in green) on the surface of an emerging Arabidopsis lateral root (plant nuclei shown in blue).

Family trees are full of surprises. That's what makes ancestry projects fun. There's usually a swashbuckler and a settler somewhere, as well as a pirate and a princess and a cowpuncher.

Surprises are found in the roots of life too—the actual roots, those underfoot essentials so easily overlooked. Recently, a team of researchers led by the DOE Office of Science's Joint Genome Institute (JGI) and the University of North Carolina (UNC) Chapel Hill took a hard look at those roots and found them indeed full of surprises.

Specifically, the researchers studied the roots of a common weed, the mouse-ear cress (Arabidopsis thaliana). The cress is a member of the mustard family and is known as the "lab rat" of the plant kingdom since it's so often used in studies.

The JGI researchers and their colleagues took a more detailed look at the roots of some six hundred cresses growing in two distinct types of soil. And in a study that made the cover of Nature (http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v488/n7409/full/nature11237.html), they found an incredible exchange of nutrients and information; an unexpected microbial marketplace whose inhabitants both provide for their own needs and contribute to the health and growth of the plant.

Roots have two distinct spaces, or niches: The endosphere, the area inside the root, and the rhizosphere, its immediate outside surroundings. Each niche has a variety of inhabitants, which JGI dug into using the power of its deep genome sequencing and microbial analysis techniques.

Image courtesy of William S. Justice @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Image courtesy of William S. Justice @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh., mouseear cress

In taking almost the equivalent of a survey, or census of those root residents, researchers found a wide range of interacting actors. Bad actors like parasites are part of the culture, but so are good bacteria that can supply nutrients, suppress pathogens, improve plant growth and even increase resistance to heat and drought.

For instance, plants depend on microbes known as rhizobium and mycorrhizae, which pull the vital nutrient of nitrogen out of the air and turn it into a form that plants can use. In return, plants supply the microbes with safety and energy. Both benefit, a relationship referred to as symbiosis.

Roots appear to keep some microbes out, while actively encouraging others in. They also seem to send out signals that encourage the growth of specific types of microbes in their immediate surroundings.

If such rich communities can grow in the roots of a simple weed, larger plants and trees may develop root ecosystems of truly staggering complexity and diversity. But beyond the simple fact of wonder lie more practical applications. By developing a better understanding of the microbes that affect the growth of other plants—say crops like corn or wheat—researchers may be able to improve their growth, or provide better care for them in times of drought.

Roots are full of surprises. But thanks to JGI and the Office of Science, some of their secrets are being revealed, an effort of digging which will benefit the entire family tree.

The Department's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information please visit http://science.energy.gov/about/. For more information about the Joint Genome Institute, please go to http://www.jgi.doe.gov/.

Charles Rousseaux is a Senior Writer in the Office of Science.